In 2014, I co-founded Silent Funny, an arts space in Chicago.

With the help of our board, neighbors, artists, curators and music programmers, we’ve coordinated dozens of exhibitions, performances, gatherings and family events for our neighbors and the greater city of Chicago.

Silent Funny is a 501(c)(3) organization and gallery in West Humboldt Park where art, artists and everyday people connect in a contemporary space that is inclusive and inspiring. Learn more.

Art Collaborators

Luftwerk, Saint Heron, Industry of the Ordinary, Amir George, Kevin Drumm, Dave Rempis, Josh Abrams, Avreeyal Ra, Joan of Arc, Tim Daisy, Greg Lunceford, Barb Koenen, Thelonious Stokes, Kiara Lanier, Claire Molek, Jake Harper, Katinka Kleijn, Juan De La Mora Jr., Brian VandenBos, Sarah Beth Woods, Jacob Kart, avery r. young, Bruce Lamont, Coppice, Bitchin’ Bajas, Haley Fohr, Califone, Matchess, Anna Cerniglia, Titus Wonsey, Colleen Plumb, Ben Lamar Gay, Vincent Smith, Theatre Oobleck, Andrea Jablonski, Margaret Bayne, Anansi Knowbody, Jane Georges, Daniel Schor, Clark Golembo, Jose Rios, Sue and Sandy, Daniel Allen, John Campos, Milton, Alderman Emma Mitts, and more.

Working with so many wonderful artists inspired me to make some art of my own.

Today’s New Shadow Sides

Gig Economy Concept Art

by Matthew Baron

with Adé Hogue

At a board meeting for Silent Funny, the non-profit arts space I co-founded, I told my fellow board members that I had an idea for an art show about the gig economy.

I couldn’t tell if they were more confused by the fact that I had an idea for a conceptual art project or that I thought one about the gig economy would be worthwhile. Saying my idea out loud came on the heels of some reflecting I’d been doing on how the gig economy companies I used impacted my life or not. Living in Chicago’s West Loop since early 2014, I got to witness the neighborhood turn into a place with easy Uber access to a hotbed of what felt like countless gig economy companies and logos keeping the lives of my neighbors churning. I began reflecting on my usage and impressions of these companies. I purchased some goods and services on a weekly basis (Via, Lyft, Prime) or multiple times a year (Airbnb). I used some services just once because I had a promo credit or emergency (Postmates, Taskrabbit). Some I hadn't used but would be open to (Instacart, Shipt). Others I'd mostly sworn off due to high fees or my interpretation of their politics or negative impact on their workers (Grubhub, Uber). I was seeing more and more of my friends both using and providing these services and, living in Chicago's West Loop, every time I left the house I was awash in a swirl of gig services: Ubers lingering on Madison, Grubhub delivery people scampering into condo buildings, friends and neighbors getting pinged: their Taskrabbit was here.

I wanted to know, from a qualitative and interpersonal standpoint, in what ways can being a gig provider affect the person’s quality of life. As a former busboy, dishwasher, waiter, caterer, and later salesperson then teacher, I had jobs where the overarching theme was to be of service to others. I was curious how this compared. And I wanted to know what the money was like.

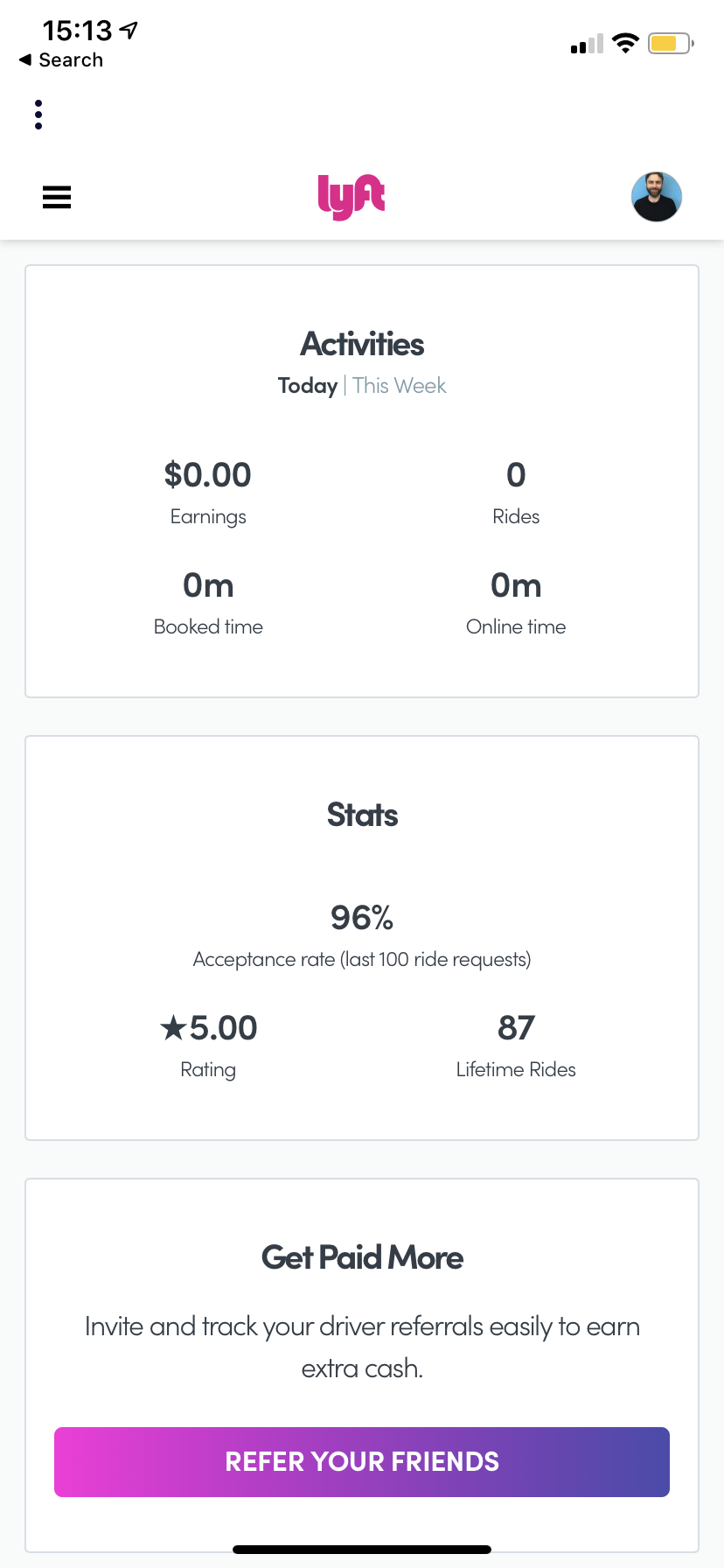

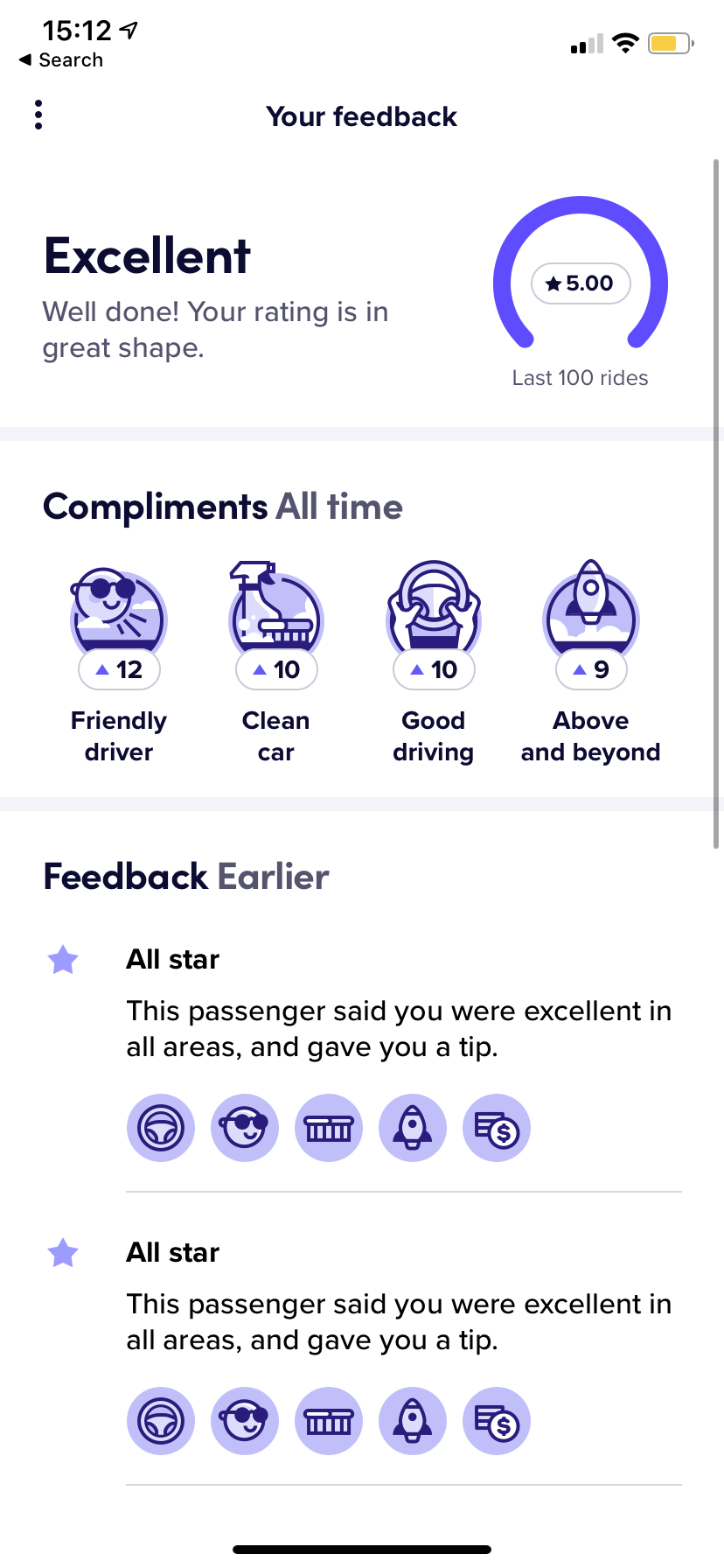

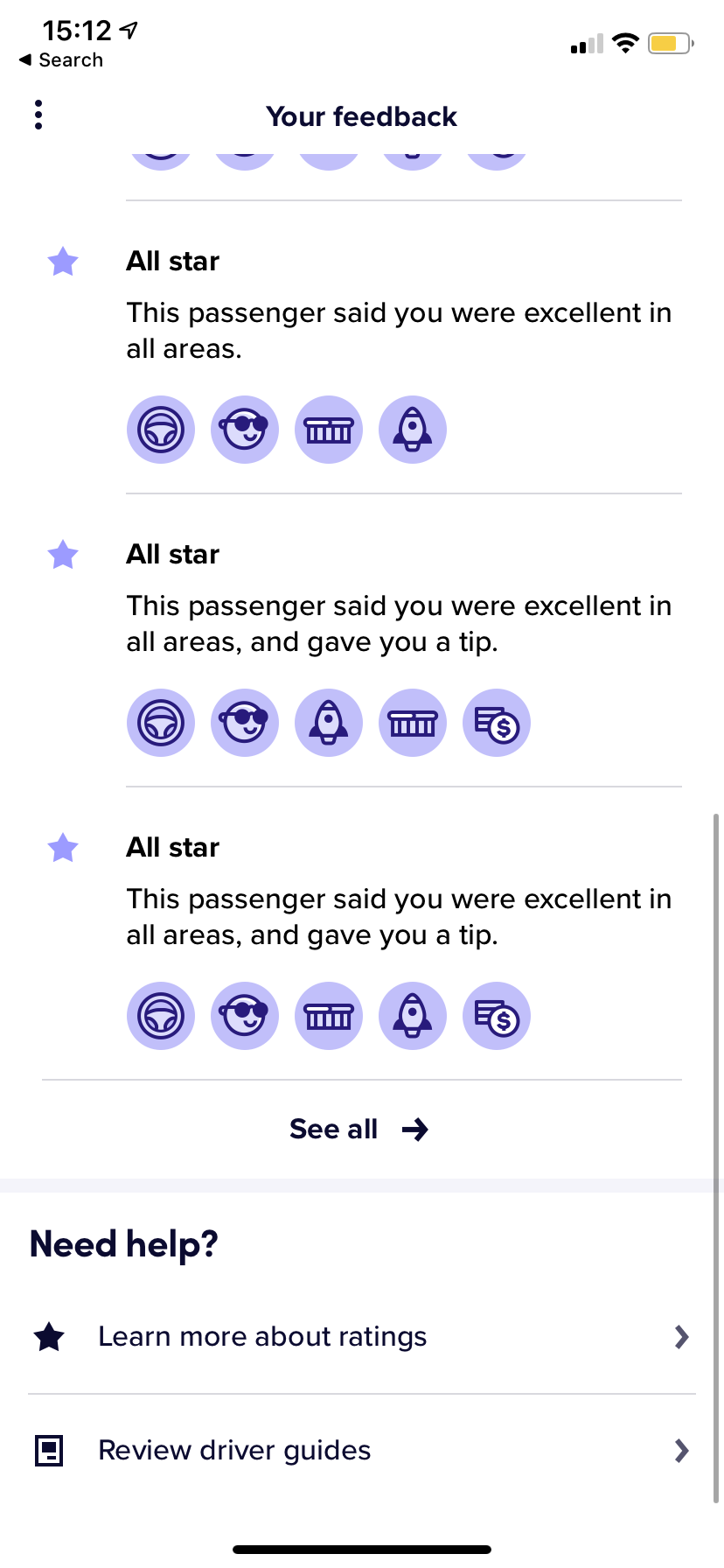

I decided to explore what it felt like on the provider's end by driving for Lyft. I have a car, love to drive, and with my experience of having cold-called every business park or office building within 30 miles of Chicago plus living in the city for almost 15 years, I know my way around. I was curious to learn first-hand if the money I paid for gas, insurance, and regular upkeep could be offset by driving for Lyft. I still worked as a teacher so I decided to work in short, structured intervals that I could extrapolate into projected financial numbers. Would it be possible to make a decent living by driving Lyft?

I took my job seriously. As a driver, I never made calls or listened to podcasts (my usual preferred ways of passing time while driving). I didn't want to alienate people by playing NPR, so I only listened to music. I felt some eye rolls whenever I'd play classical radio so I shifted to Spotify. My favorite albums to drive were the new Solange’s A Seat at the Table and David Berman's Purple Mountains record. When the albums finished, I’d let them repeat and start over. I'd speak with passengers but would adhere to Lyft's guidelines about being friendly, but don’t keep talking if the passenger doesn’t reciprocate. A pretty good rule of thumb for life in general. I only got scared once, when a mom and her two kids tumbled into the back seat and didn't put on their seatbelts. When driving friends and family I won’t put the car into drive until they’re buckled up. Though it was my professional responsibility, I didn’t want to upset my customer or come across as holier than thou.

The first theme I noticed about the people I drove was that many worked hourly jobs at big box stores or restaurant chains. They used Lyft to get to or from work. I wondered if and how someone could spend an approximate hour’s worth of their pay on a ride home. I drove others on cumbersome errands, like a man without a car who needed to pick up his son from the Kedzie CTA Station, 10 miles south of his pickup, before turning right back up north with his son in tow. I took some out-of-towners from Wrigleyville—a dad and his kids who had never been to Chicago or a Cubs game before—back to their Holiday Inn Express in Niles. Once I drove a couple home from a date from a restaurant so close to their apartment I judged them for not walking. I only drove someone to an airport once, O'Hare. She was an opera singer trained in the Alexander Technique breathing method, something I’d just heard of and had booked a lesson for myself for the following week when I’d be in New York City.

Despite not seeing how I could ever earn enough money to afford my relatively minimal expenses (no mortgage, no kids) I loved driving for Lyft. I was completely present while on the job. I only focused on the safety of my passengers (except the seatbelt time), my surroundings, and the music. It was a highlight of my day when I clicked open the app and used blue painter’s tape to affix the silver and purple signs to the inside of my hatchback’s rear window. (I always took the signs down because I felt embarrassed of how it looked to be driving for Lyft when I had a full-time job as a teacher. I wonder why things I love and feel intrinsically good about would bring on that feeling of shame, especially when waiting for my first ride of the day felt like being in line for coffee.

My main takeaway from this experience is that I would encourage anyone who hasn't already to participate on both ends of the gig economy at some point in their lives. Providing a service felt more fulfilling and internally rewarding than whatever I would click on to fill my whims as a purchaser.

I wanted to parlay my experience as a Lyft driver into a more encompassing art project about the gig economy in general. I wanted to figure out a way to portray both sides of the gig economy based on my recent experience in a way that could get myself and others to think about the way we understand the logos that have become a part of many people’s lives.

I decided to pick ten of the most well-known gig economy organizations and co-opt their logos. I worked with graphic designer Adé Hogue to customize the logos with new company names, all of which have the same number of letters as the actual name. I wanted the new names to serve as effective double entendres, names that as someone who provided and received gig services, now has a richer understanding of the layered meanings of what it means to use these companies. Both parties in a gig economy transaction participate for a reason. The new company names shift meaning depending on whether you are the service provider or consumer. I believe they can also offer a glimpse of empathy for people on both sides of the transaction regardless of one’s experience using these services.

This show was conceived and completed (but not shown) over the course of the year from Fall 2018 through Fall 2019. I sat on sharing the show given a rupture in my own life and felt excited to share it when possible. But now, since the entire world’s lives have been ruptured due to the pandemic, the poignancy of what the gig economy means, the wages, Silicon Valley, the relationships between providers and users, everything has become much more salient and politicized. Plus the demand for these services have changed in ways no one could have predicted, which shows me that even the double entendre words I selected for the logos can have many more meanings, depending on the state of our world.

In the end, when engaging in the gig economy, I've discovered that we are both users and providers regardless of what side we are on. When using a service I am providing an opportunity to be of service and earn money for someone else; when providing a service I must use the system as it is–there’s not a lot of room for me to impart creativity or personality beyond having mints and water (and now masks) for passengers.

But the connection I felt with passengers, their need for me, shifted the feelings I had before I ever drove. I looked at the provider, sadly, as a subordinate, a hired hand. But after being a driver, in that role I felt surprisingly high levels of worthiness and well-being. My confidence rose as I carted people around Chicagoland in my clean black Honda Fit, even though when I extrapolated the numbers, I couldn’t imagine how driving full-time could be financially viable given the expenses I’d have to put towards keeping my car alive. I also wondered if the joy I felt ever exceeded that of those making the real money off these services, the creators. As with most of my life experience, it’s experience and interaction, not higher numbers in my bank account, that brings me the most happiness and fondest memories.

As with everything, status and need is constantly in flux. Today, when writing (June 2020), Airbnb and Lyft are far less popular than Grubhub and Instacart. I imagine the scale will tilt again but in which way I cannot predict; I won’t believe anyone who says they know.

When this project started, one of the less recognizable logos or company names, when compared to Airbnb and Uber, was the company Postmates. I had a somewhat sour view of this company because, after having used the app once to get Whitney a piece of chocolate cake from Whole Foods (I’d gotten a free trial gift card from a cafe counter), I felt rotten for having someone deliver something so frivolous (and for no doubt for not a lot of pay). I couldn’t predict how the reappropriated name I gave this company in Fall 2019 would become one of the most significant words in our current lexicon. It’s what we call those who’ve shown up to work in the outside world every day since the pandemic began, those our society seemingly reveres the most–the doctors, the grocery store workers, the bus drivers, the ones who got first access to the vaccine, those who help keep us alive physically and mentally and (whether I admit it or not) spiritually. The word: Essential.